Originally Posted on January 12, 2021, now updated

A lovely Alexandrian Tetradrachm of Gordian III (Emperor, 238-244 CE), notable for its important provenance, being illustrated and cited in reference literature over the past 120+ years, and having an unpublished obv. legend variant known from only one other specimen (see Historical Notes and Numismatic Notes below).

Roman Provincial. Gordian III (238-244). Billon Tetradrachm (23mm., 12.35g, 12h). Struck in Egypt, Alexandria, 243-4 CE.

Obverse: Α Κ Μ ΑΝΤ Γ-ΟΡΔΙΑΝΟϹ ƐΥ (see Numis. Notes below). Laureate, draped & cuirassed bust of Gordian right, seen from behind.

Reverse: Bust of Helios facing right, radiate & draped, seen from behind. In fields, L-Z (Regnal Year 7).

Published: Dattari [1901] 4731 (this coin cited, incorrect legend break described); Dattari-Savio [1999, 2007] plate 252, 4731 (this coin illustrated); RPC VII.2 3874 (this coin illustrated online, #11417 [print vol. due in 2022]); Vogt II [1924] Alexandrinischen p. 140 (this coin cited); Klose & Overbeck [1989] Ägypten zur Römerzeit p. 36, No. 97 (this coin cited); SNG Hunterian [2008] p. CCCVIII (this coin cited).

Further Refs: Milne 3466; BMC Alexandria 1859; Emmett 3407; K & G 72.137; Feuardent [1869] v2, p. 210, 2743; see especially, CNA XVIII [3 Dec 1991], Lot 443 = Col. J. Curtis [1990] #1265 (same obv. die & only other published specimen w/ same legend break); on the significance of obv. legend breaks, see Milne [1918] “The Shops of the Roman Mint of Alexandria” (JSTOR 370158).

Provenance: Ex-Naville Numismatics (London) Auction 60 (27 September 2020), #308; ex Giovanni Dattari (1858-1923) collection, before 1901.

Historical Notes: Giovanni Dattari (1858-1923) was an Italian numismatist and antiquities trader, and amateur scholar, living in Egypt at the turn of the century. Today, the control he exerted over the Egyptian antiquities and coin trade would be impossible and doubtless considered highly unethical, but much of our current knowledge about Roman Egyptian coins is based on his extensive work. His catalogs remain standard references for Alexandrian coinage.

The American Numismatic Society Magazine cover story from Vol 17 [2018], Issue 2 – .pdf available on Lucia Carbone’s academia.edu page – gives an excellent background. For those who read Italian, Adriano Savio’s biography of Dattari and his collection is available online.

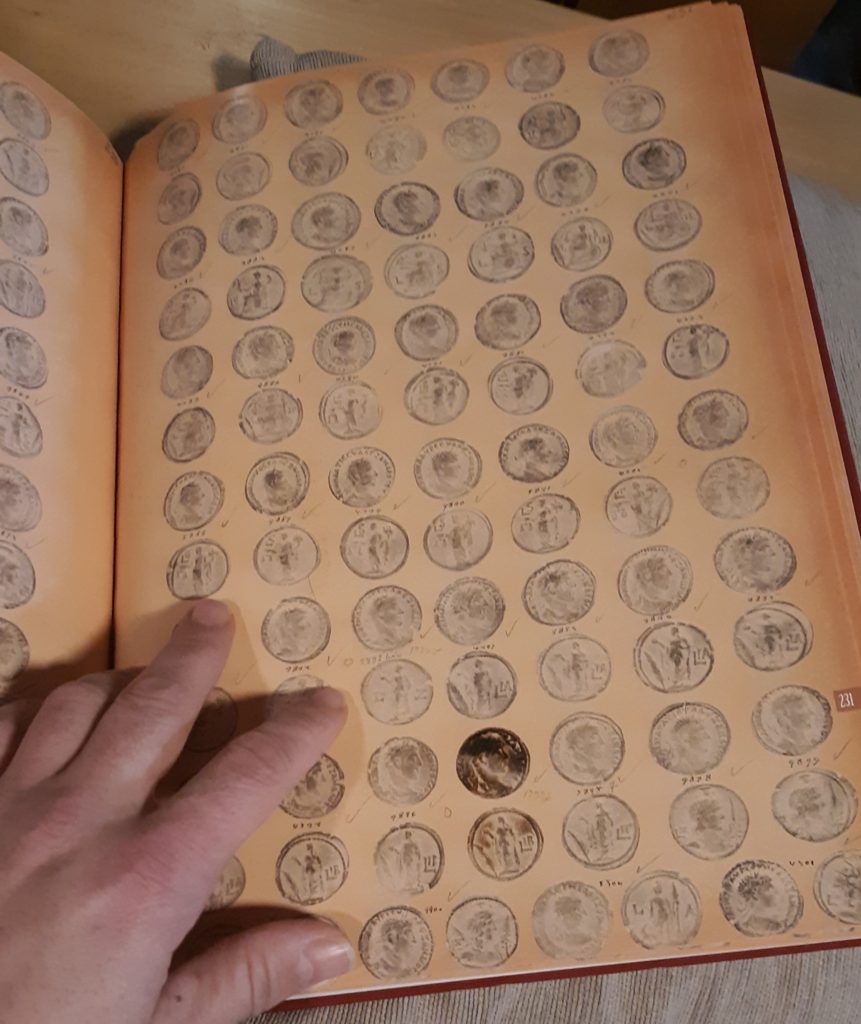

Dattari’s collection of Alexandrian coins reportedly consisted of 13,000 coins when he died, by which time he had already sold or donated thousands more. He cataloged at least 12,512 in his combined volumes, Numi Augg. Alexandrini (1901) and its second volume of illustrations (pencil rubbings of plaster casts), posthumously edited by Adriano Savio (1999/2007), who tracked down an additional 700 illustrations, totaling >13,200. In the 1901 vol. (which cataloged the first 6,580), he mentioned an additional 19,320 Roman Imperial coins, plus his collections of Greek coins.

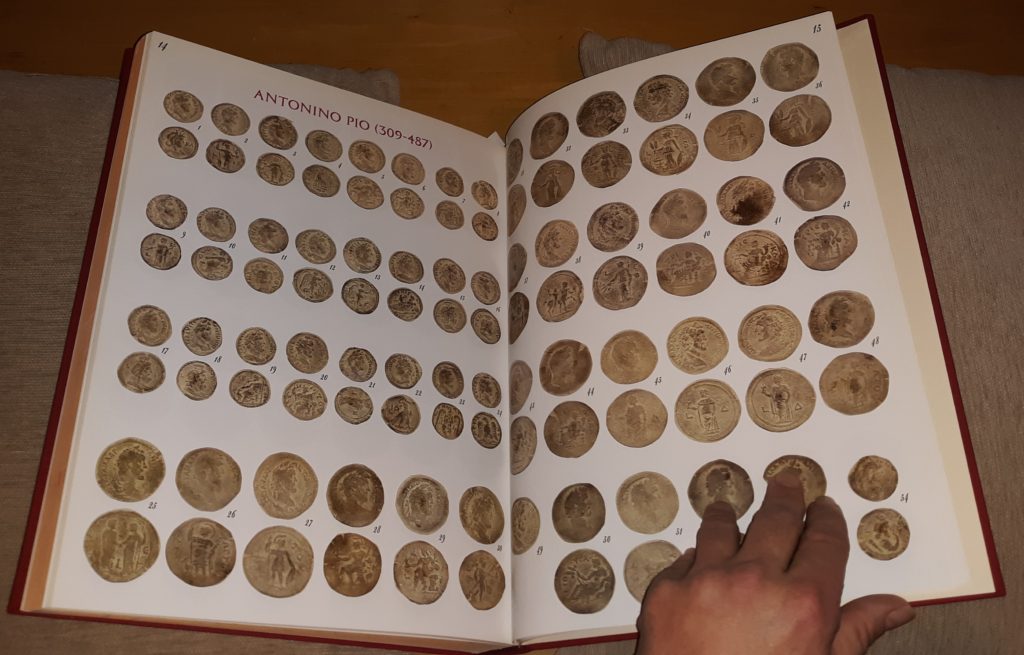

Another Alexandrian Helios Tetradrachm, ex-Dattari Collection, illustrated in Savio (pl. 210, 9612) & RPC Online. Commodus, 189/190 CE.

Ex-Naville 60 (27 Sep 2020), Lot 296 & Naville 51 (21 July 2019), Lot 365.

Numerous Dattari coins are now in public collections, including tens of thousands he acquired as an agent for museums during his lifetime (his British Museum bio links 373 objects), and thousands more either donated by the Dattari family or purchased on the open market after his death.

Among them: Smithsonian Institute, Washington, DC; Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome; Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (though provenance not noted online); University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; the British Museum, London; American Numismatic Society, New York (though only dozens explicitly provenanced as such in Mantis); Art Institute of Chicago (especially those gifted by R. Grover, only some of which were deaccessioned and sold at Gemini XIII in 2017).

Additionally, 5200 of his Late Roman Bronze Coins from the Alexandria mint are now at the KBR (Belgian Royal Library, Brussels Coin Cabinet). (See Fran Stroobants’ article on “Alexandrian nummi in the collection of the Coin Cabinet of the Royal Library of Belgium.”)

By now, unfortunately, many or most in private collections have lost the Dattari pedigree, but the illustrations in Dattari (1901) and Savio (1999/2007) allow collectors and dealers to retrieve it. In the illustration below, two of the coins were sold without the Dattari provenance but I was able to identify them using the Savio volume. (In fact, both coins had duplicate listings in RPC – two listings under their Dattari numbers, plus two under their recent collections/sales – until I alerted the editors that they were one-and-the same!)

The Hadrian AE Drachm (ex-Righetti Coll.) and Severus Alexander BI Tetradrachm (ex-Rocky Mountain Coll.) were not recognized as Dattari Collection in the sales where I found them (nor in RPC).

The Antoninus Pius Tetradrachm was once in the Art Institute of Chicago Collection, donated by Robert L. Grover, sold at Gemini XIII.

Given their vast quantity, pedigreed Dattari coins remain readily available, though. When judging examples, important qualities are strength of documentation, whether cited or illustrated in Dattari (1901) or Savio (1999/2007), and where in his collection they fit (e.g., Alexandria, Imperial, other). Personally, I’ve been unable to acquire a copy, but a fantastic supplement to the Dattari catalogs is Giuseppe Figari & Massimo Mosconi’s 2017 volume, Duemila Monete Della Collezione Dattari (Genoa: Circolo numismatico ligure “Corrado Astengo”). [If anyone has a copy, I’d love to buy it — or many copies if they can ship together!]

A few outlets are worth watching: Naville (UK) has auctioned a vast consignment of Dattari’s coins in recent years (I suspect they’re running out, but they make frequent secondary appearances); CNG (USA) has recently sold many of Dattari’s Alexandrian, and many Imperials, as has Jesús Vico (Spain); many have appeared at Kuenker (Germany) and Roma (UK), and other firms that emphasize provenance. Examples can be found on VCoins, MA-Shops, and from dealers such as FORVM (Dattari is not listed among featured collections/pedigree, but one was just sold from their “plate coins” page).

Numismatic Notes: When Dattari published this Gordian III / Helios Year 7 tetradrachm in 1901, the type had been referenced at least twice before in the literature (Dattari, p. 324, #4731; Poole [1892] BMC Alexandria #1859; Feuardent [1873] Numismatique : Égypte Ancienne, v. 2, #2743).

What Dattari failed to note in 1901 was that the coin had an unusual and very rare obverse legend break for this type (Γ – ΟΡΔΙΑΝΟϹ rather than ΓΟ – ΡΔΙΑΝΟϹ, as on almost all other examples). In fact, I can find only one other example, No. 1265 of the Col. James Curtis Collection (same obv. die). Although cited in his 1969 and 1990 books on The Tetradrachms of Roman Egypt, neither catalog gives the obverse legend or illustrates the coin. Its only appearance, to my knowledge, was at CNA Auction XVIII (3 December 1991), Lot 440.

Obverse legend breaks are usually treated as the insignificant whims of the engravers. In this case, though, they may have a specific significance. According to Milne’s (1918) article, “The Shops of the Roman Mint of Alexandria” (Journal of Roman Studies, JSTOR 370158), the obverse legend breaks for Gordian III (and some other reigns) indicated different workshops at the Alexandria mint.

Though only the second example for this obverse die for this issue (i.e., Helios / LZ) – and thus, likely only the second example of its type from that workshop – this coin is die-linked to several other reverse types from Year 7.

Of the 10 examples illustrated on RPC Online and several others I’m aware of in commerce, there are at least four other obverse dies, all sharing the same legend arrangement (a typical example illustrated below). None of them shares a reverse die with my specimen or the Col. J. Curtis specimen.

A Potential Test of Milne (1918): I have yet to find anyone following up on or refuting Milne’s 1918 hypothesis that legend breaks represent Alexandrian workshops. But here is an instance where two specimens (Dattari 4731 & Curtis 1265) suggest a way to test his hypothesis. For this type (Helios Tetradrachms of Year 7), there are two reverse dies used by the potential “G-” workshop that are not known to be paired with obverses from the “GO” workshop (and vice versa, the reverses used with “GO” aren’t used with “G-“).

This pattern is consistent with Milne, but it’s too small a dataset to provide much positive support.

The same “G-” obverse die was also used with various other reverse types for Tetradrachms of Year 7 (perhaps other “G-” dies are present, too). At least 13 reverse types are represented in RPC Online for Year 7 of Gordian III, with at least 275 specimens (not all of them illustrated). I haven’t (yet) done the work myself, but the die-linking test seems clear. If there are no reverse-die-links across the “G-” and “GO” obverse dies, then Milne’s hypothesis is very strongly supported. If “G-” and “GO” dies are linked by shared reverse dies, then one must abandon Milne (or at least imagine a much diminished relationship between workshops and die variants).

Other Examples: RPC Online illustrates 10 examples of the Dattari 4731 type and cites an 11th. (If it’s out yet, I haven’t seen the print vol. of RPC VII.2.) Besides the ones in RPC, a few specimens have appeared in sales, either in catalogs or online. In addition to Curtis #1265 (CNA XVIII, 443), there was a nice example sold by Mike Vosper (MA-ID: 679900844, “Ex. I Jones Collection”; archived in case removed from web). An example not noted elsewhere was submitted by Carpediem Numismatics to Wildwinds in 2017.